A Possible Fix For Scientific (and Academic) Publishing

Originally Published on the Peer Review Blog.

Scientific and academic publishing is broken. The vast majority of the journals have been privatized by publishers who charge astronomical fees for access to the literature.

The fees have gotten so high that even well funded universities have started to walk away from negotiations. Universities with less funding have long been unable to afford them. The average citizen has no hope of affording them.

With the results of the scientific process locked away behind paywalls, science is no longer an open and transparent process. Worse, the ultimate deciders of policy in a democracy, average citizens, are being denied access to the primary source materials necessary to make good policy decisions.

The Open Access movement has been trying to solve this problem, but it has mostly stuck to the existing model of hiring editors to manually match reviewers to papers, creating high overhead. To fund their operations, most Open Access journals have flipped the business model from fee for access to fee for publish. This has created a whole host of new problems, including the rise of predatory journals that are willing to publish almost anything by anyone who can pay.

The ultimate effect of pay-to-play is that the traditional peer review and refereeing process has broken down. If a dishonest researcher gets rejected from a reputable journal, they can take their paper to a pay-to-play journal and have it published there. With over 10,000 academic journals, it’s impossible for the lay public to track which journals are reputable and which are not. As far as the public is concerned, a published paper is a valid paper.

This is a proposal for a software platform that may help the academic community solve these problems, and more.

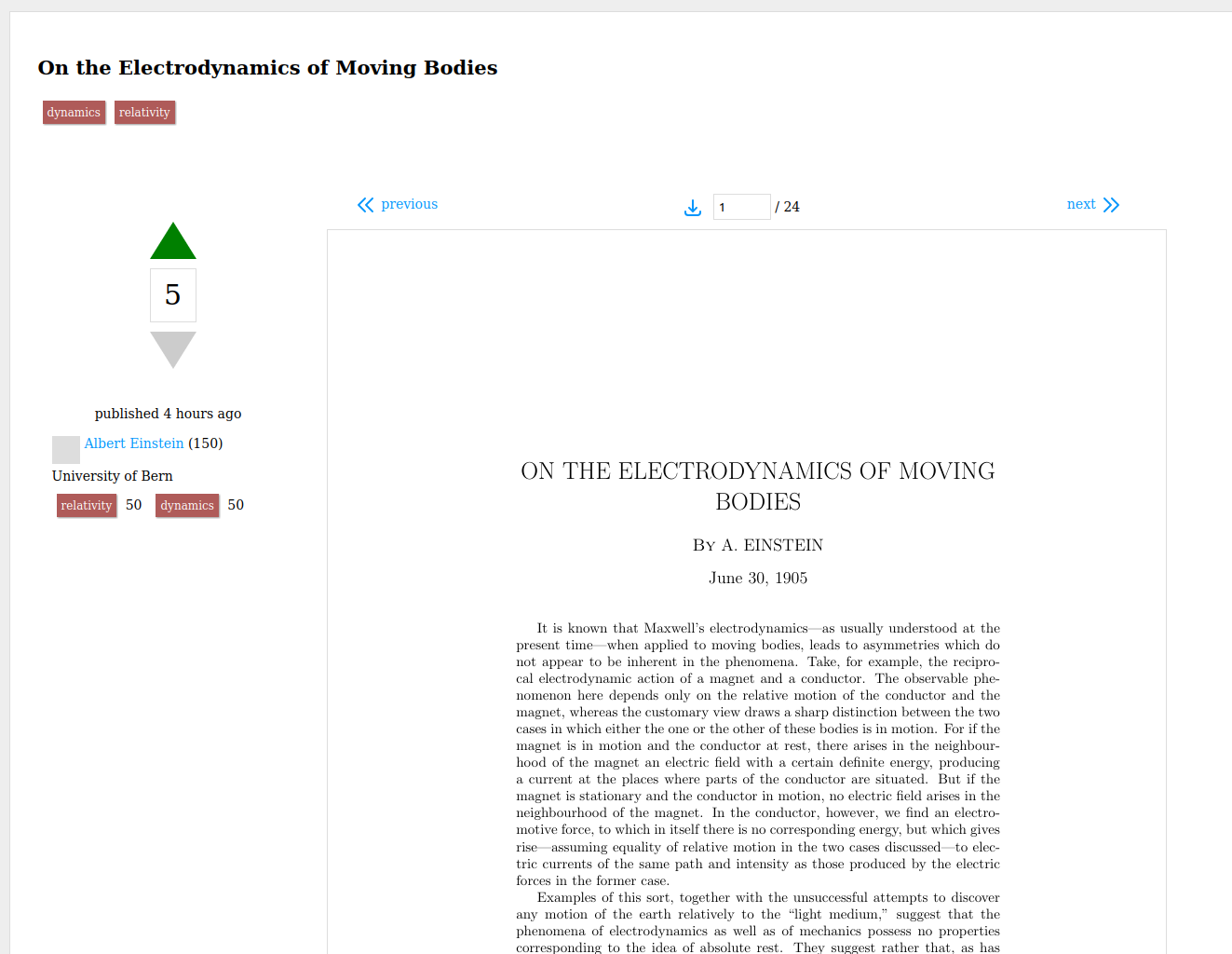

Peer Review - A Proposed Publishing Platform

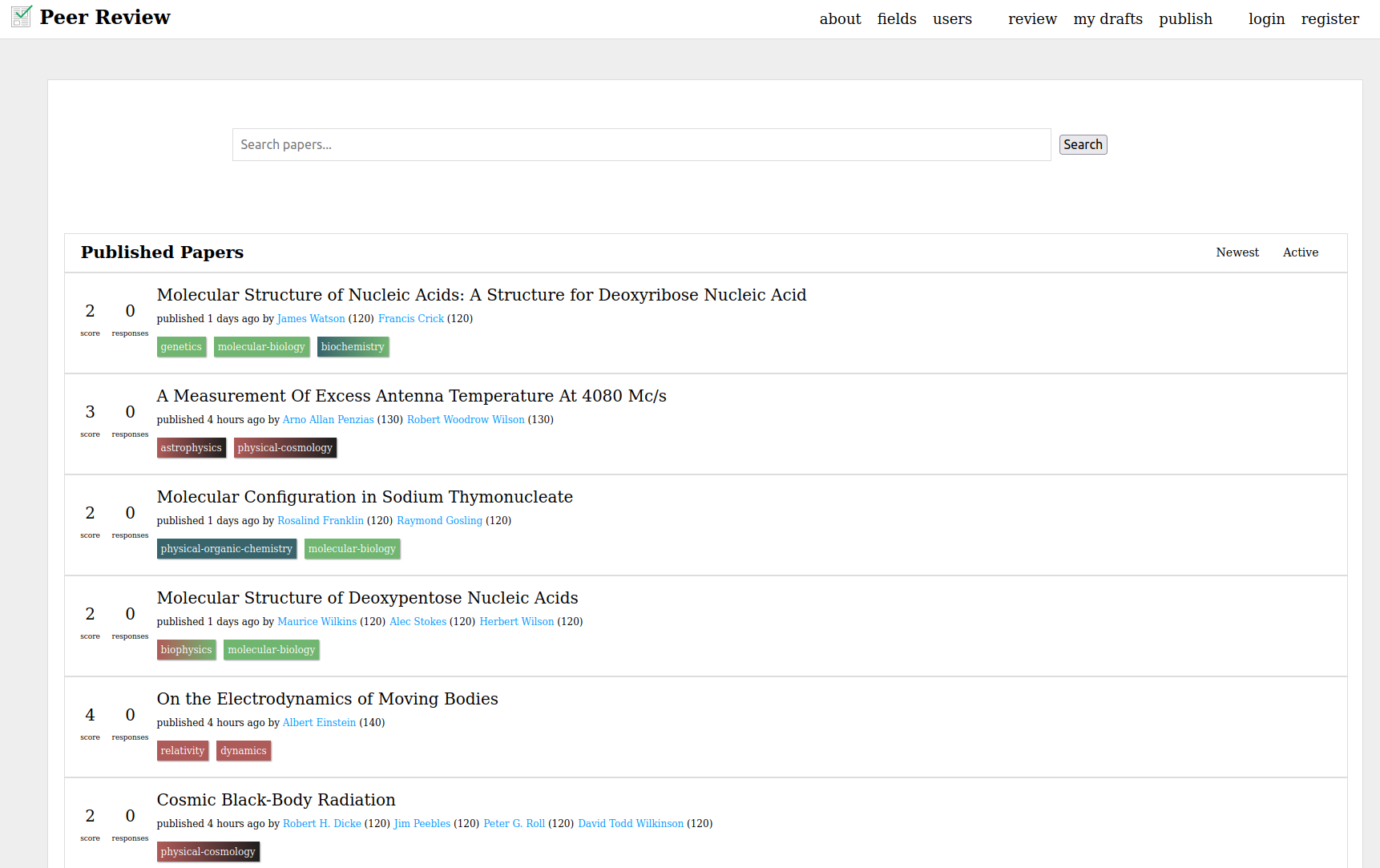

Peer Review is a diamond open access (free to publish, free to access) academic publishing platform with the potential to replace the entire journal system.

Peer Review allows scholars, scientists, academics, and researchers to self organize their own peer review and refereeing, without needing journal editors to manually mediate it. The platform allows review and refereeing to be crowdsourced, using a reputation system tied to academic fields to determine who should be able to offer review and to referee.

The platform splits pre-publish peer review from post-publish refereeing. Pre-publish review then becomes completely about helping authors polish their work and decide if their articles are ready to publish. Refereeing happens post-publish, and in a way which is easily understandable to the lay reader, helping the general public sort solid studies from shakey ones.

Peer Review is being developed open source. The hope is to form a non-profit to develop it which would be governed by the community of academics who use the platform in collaboration with the team of software professionals who build it (a multi-stakeholder cooperative).

Since the platform crowdsources the work of review and refereeing, and because it can potentially handle all academic and scientific fields on a single platform, we could eliminate most of the overhead of academic publishing. Meaning Peer Review could be initially funded with small donations from the scholars using it. If the platform were to eventually replace the entire journal system, it could be funded by the universities for a tiny fraction (1% or less) of what they are paying for publishing now.

Peer Review is currently at the alpha stage of development, most of the core features are functional in a proof of concept. They need testing and hardening, and a number of functionality gaps need to be filled in. I hope to reach a closed beta in the next few months. And an open beta several months after that. I’m seeking academics to give feedback on the concept, help test the alpha, and help us prioritize the roadmap for the closed and open betas.

If Peer Review succeeds, there are any number of ways we could take it. It could potentially solve the file drawer problem from the beginning, by simply giving scholars a place to submit, get immediate feedback on, and publish file drawered papers. We could explore building systems to help incentivize and highlight replications - linking replications to the studies they are replicating and giving replications a reputation bonus. We could build systems to assist with data sharing and funding transparency. We could even explore automating some of the grunt work of maintaining the academic literature - such as generating automated literature reviews. And we could work to make the academic literature more accessible and understandable to general public.

How It Works - The Overview

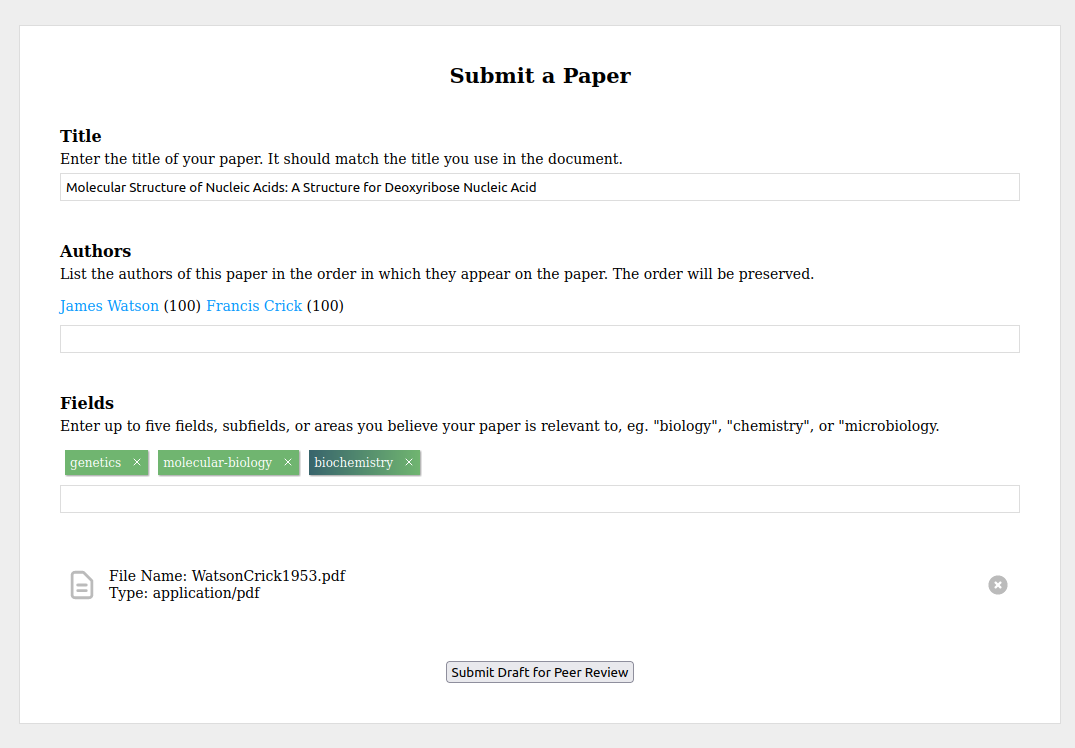

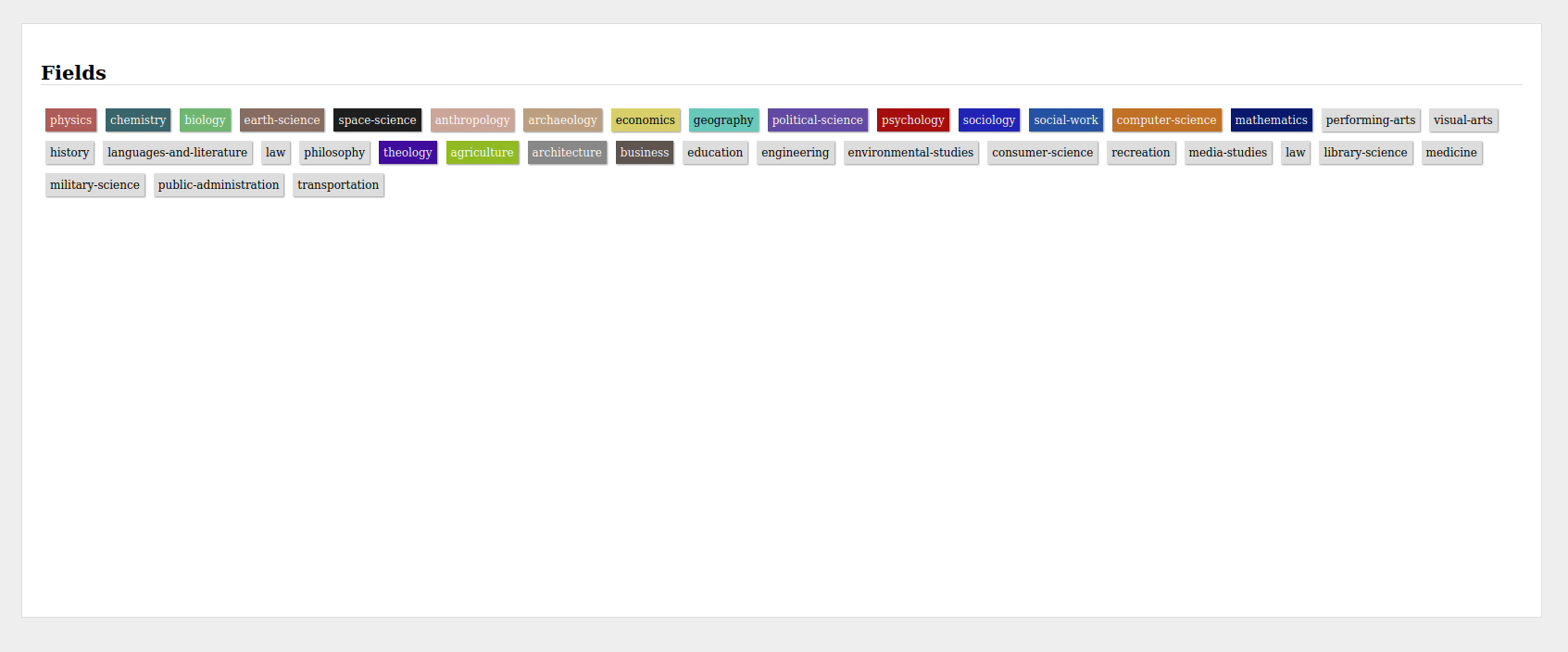

Here’s how the platform works in detail. When you have a draft of a paper you’re ready to get feedback on, you submit it to the platform. You give it a title, add your co-authors, and tag it with up to five fields or disciplines (eg. “biology”, “biochemistry”, “economics”, etc).

The fields exist in a hierarchical graph, which is intended to be evolutionary. Each field may have multiple parents and many children - eg. “biochemistry” which is a child of both “biology” and “chemistry”. The hierarchy can go as deep as it needs to. We’re initializing the field hierarchy using Wikipedia’s outlines of academic disciplines, but the intention is for the 1.0 version to include the ability for scholars to propose new fields or edits to existing fields, along with a proposed place in the hierarchy, and for their peers to confirm the proposals.

When reputation is gained in a child field, it is also gained in all of that field’s parents. So a paper tagged “astrophysics” also gives reputation in “physics” and “space-science”. Reputation is primarily gained through publishing and receiving positive feedback from your peers during post publish-refereeing - more on that later.

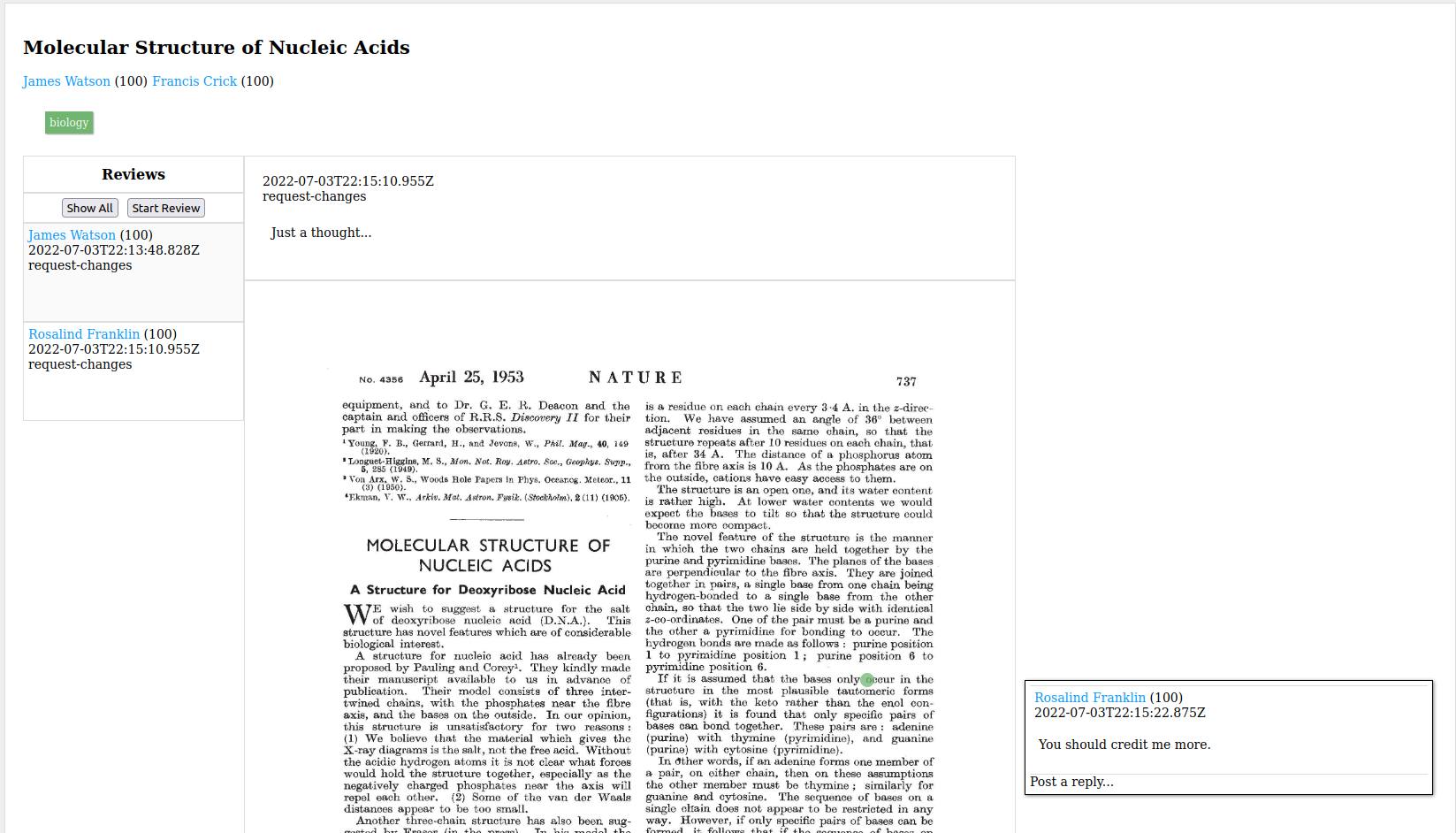

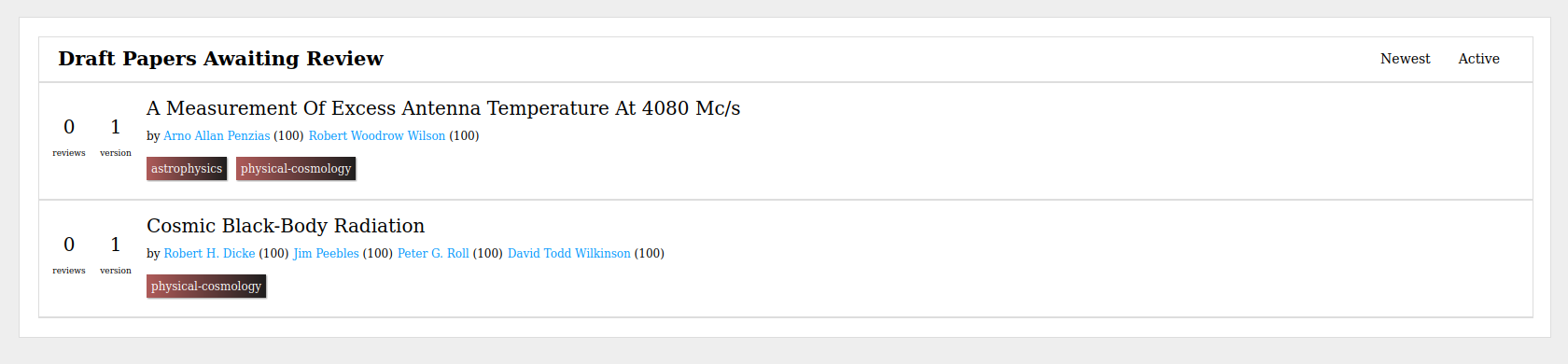

When you hit submit, the draft goes into the review queue. Here other scholars who have enough reputation in any of the fields you tagged the paper with can see the draft and offer feedback on it.

This system gives scholars an enormous amount of control over who they solicit feedback from. By choosing how high up the field tree they go, they choose how wide to cast their net. Because they can add up to five fields (which don’t have to be related) they can easily request interdisciplinary feedback.

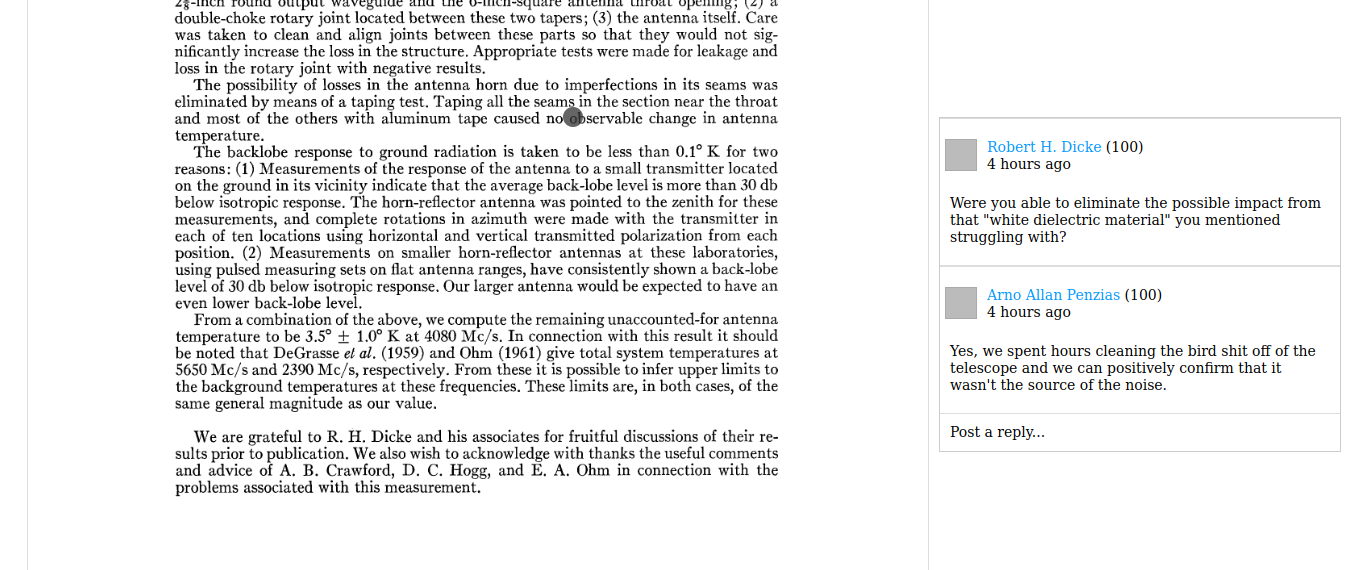

Reviewers can click anywhere on the document to leave comments.

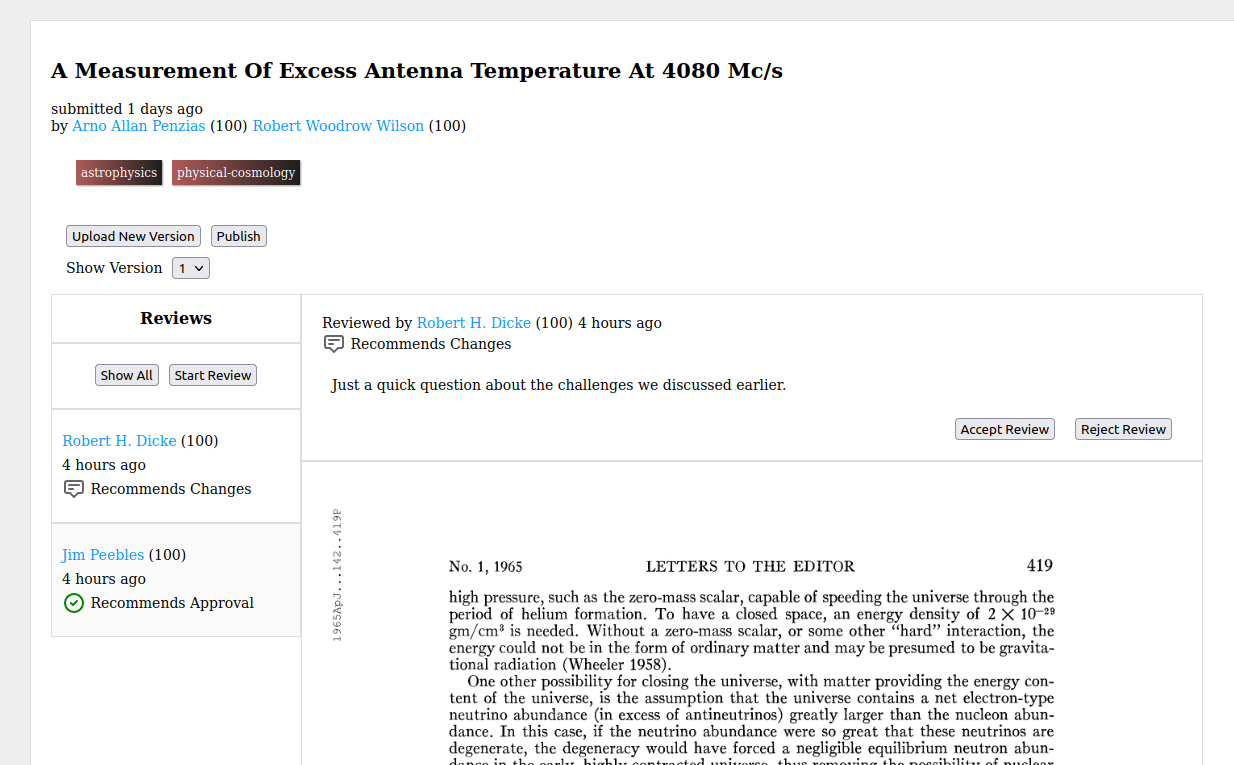

When they are ready, reviewers submit their review with a summary and a recommendation. The possible recommendations are:

- “Recommend Approval” meaning that this draft is ready to publish.

- “Recommend Changes” meaning that they think it’ll be ready to publish after the recommended changes are made.

- “Recommend Rejection” meaning that they don’t think this paper is worthy of publishing, or could be made publishable.

- “Commentary” which is just a way to offer feedback and commentary with out a specific recommendation.

Authors can then mark reviews as “accepted”, indicating that they found them helpful, or “rejected” indicating that they were not helpful. Reviews that are “accepted” grant the reviewer reputation in the fields the paper is tagged with (and their parents). Reviews that are “rejected” grant no reputation, but don’t remove it either.

As the review process goes along, authors may upload additional versions of their paper and request new rounds of review feedback for each version uploaded. Reviewers may offer as many reviews to each version as needed, but only gain reputation for a single accepted review on each version.

When the authors are ready, they hit “Publish” and their paper is published and live to the world.

This puts the pre-publish review process entirely in the hands of the authors. It gives reviewers an incentive to give solid, constructive review feedback - and rewards good reviewers for their efforts with recognition of their contributions. It treats review work as a valuable contribution to an academic field alongside publishing.

Refereeing begins once the work is published.

At that point, peer scholars with enough reputation in the fields the paper is tagged with can vote the paper up or down. Up votes increase the paper’s score and grant the authors reputation in the tagged fields. Down votes decrease the paper’s score and the author’s reputation in the tagged fields.

Up votes should be given based on an objective assessment of the paper’s quality. Is this good science? A well constructed argument? Much of the same criteria currently used to determine whether a paper should be published in a well refereed journal, should be used to determine whether a paper should be upvoted, downvoted, or simply left with no score. Instead of that judgment being passed by a handful of reviewers selected by a journal’s editor, it will be collected from the entire community of the fields the paper was submitted in.

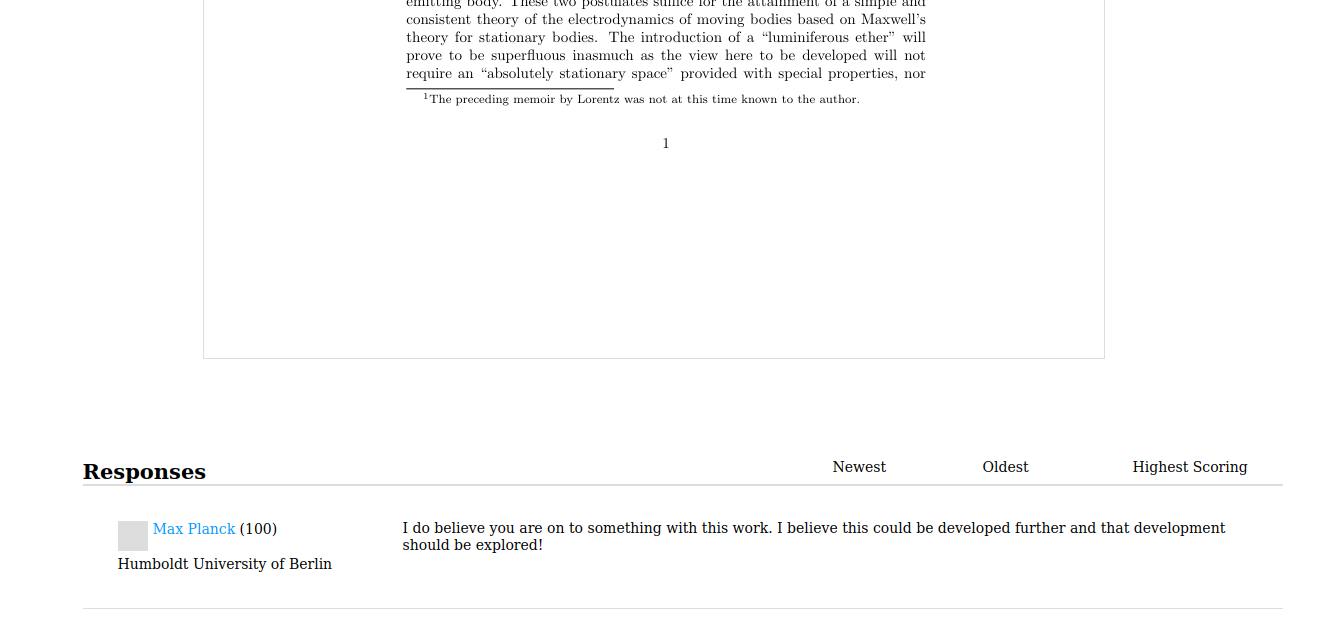

Peers can also post a single response to each paper, outlining their feedback and reasons for voting how they did (or not voting at all) in public. Down voters will be strongly encouraged to post a response explaining their downvote.

In this way, the refereeing process is made transparent and easy for the public to follow. A down voted paper should be treated with skepticism. An up voted one is trustworthy. The responses help add context and clarity.

All papers submitted to Peer Review are published under the Creative Commons Attribution License, meaning the work can be freely distributed, remixed, and reused as long as the authors of the original work are attributed.

It’s important to emphasize: Peer Review is intended to be the final publish step. It is not a pre-print server. It is an attempt to replace the journal system with something open to its core, scholar lead, and collectively managed by the scholar community.

Who Are You?

My name is Daniel Bingham and I’m the developer of Peer Review. I grew up in an academic family (my mother and father are both professors and my brother got his PhD), but went into software engineering. I taught myself to code at age 12 and have been in professional software development for well over a decade.

My most recent role was Director of DevOps at Ceros, a mid-sized software company. I built and lead the department which developed and maintained the cloud infrastructure and deployment pipelines for the Ceros Studio and MarkUp. Before building the DevOps team, I was a full stack developer at Ceros helping to build the Ceros Studio.

When I’m not writing code, I’m very involved in local policy. I’ve worked closely with representatives of Bloomington, Indiana’s municipal government on climate, transportation, and housing policy. I’ve served on government task forces and on the boards of local non-profits, including a three year term as president of the board of our local 501(c)3 affordable housing cooperative.

I’ve been dreaming about Peer Review for years. In my role as a policy advocate, I needed access to the research literature, but struggled to get it. As I pondered potential solutions to the problem of open access, the tools I used on a daily basis as a software engineer inspired the concept that became Peer Review.

I have a deep commitment to democracy, and I am as excited about the potential to build a scholar and worker governed organization around the platform as I am to build the platform.

Where Do Things Stand and Where Are They Going?

I am currently the only developer working on Peer Review full time. There are a small handful of volunteers who’ve offered part time help.

I have the alpha version of Peer Review up on a staging server. I’m looking for scientists, researchers, scholars, and academics from all disciplines who are interested in exploring the alpha and giving me feedback on the concept and where to go next.

Could this work the way I think it might? Are there things I’m not thinking of? Problems I haven’t foreseen? Aspects of the academic publishing system I am unaware of and that Peer Review doesn’t account for? Broadly speaking, am I going in the right direction?

I have a roadmap of features I need to put in place before we can begin a closed beta, and a significant amount of hardening and bug fixing to do as well. I hope to reach a closed beta in the next couple months. I’m also soliciting sign ups for the closed beta. Peer Review will only be as good as the community that forms around it, so - if the direction I’m exploring does indeed hold promise - I’m hoping we can start building that community now.

After the closed beta period I intend to do an open beta, where the platform is opened to any who would like to use it (while still understanding that it is not completely finished or polished).

You can view the roadmap on GitHub. If you’re unfamiliar with the process of software development, please keep in mind that the roadmap is a very rough estimate and that it is constantly in flux.

I’m also looking for feedback on that roadmap, are there features which aren’t currently included that should be considered for the closed beta? For the open beta?

If you’re interested in exploring the alpha and giving feedback, want to participate in the closed beta, or want to be notified when we reach open beta, please fill out this form! You can also use that form to give feedback on the initial concept with out signing up for anything.

If you think I’m on to something and you want to see Peer Review grow, please consider supporting the development effort! Right now my family (my wife, my daughter, and I) are living on savings. I’m hoping to raise enough through donations to be able to commit to working on it full time, indefinitely.

I need to raise $8000 / month to make that commitment: $5500 of monthly living expenses, $1500 to cover health care, and $1000 to cover the initial cloud infrastructure costs for site hosting.

You can support me on GitHub Sponsors. You’ll need to make a GitHub Account, but it’s free.

If we successfully raise that much, I will form the non-profit. If we raise substantially more than that I will hire additional engineers, designers, product managers, devops, and QE to help with development. I will also be pursuing grant funding once we reach the closed beta period. Any leads in that direction would be much appreciated.

If you have questions, ideas, suggestions, criticisms, feedback of any kind, grant leads, or offers of help that don’t fit into the form linked above, you can contact me at contact@peer-review.io