Can We Help Scholarly Journal Editorial Teams Escape the Commercial Publishers?

This post is the third in a series about reforming academic publishing:

- Crowd Sourced Review Probably Can’t Replace the Journals

- Why isn’t Preprint Review Being Adopted?

- How Can We Help Journal Editorial Teams Escape the Commercial Publishers?

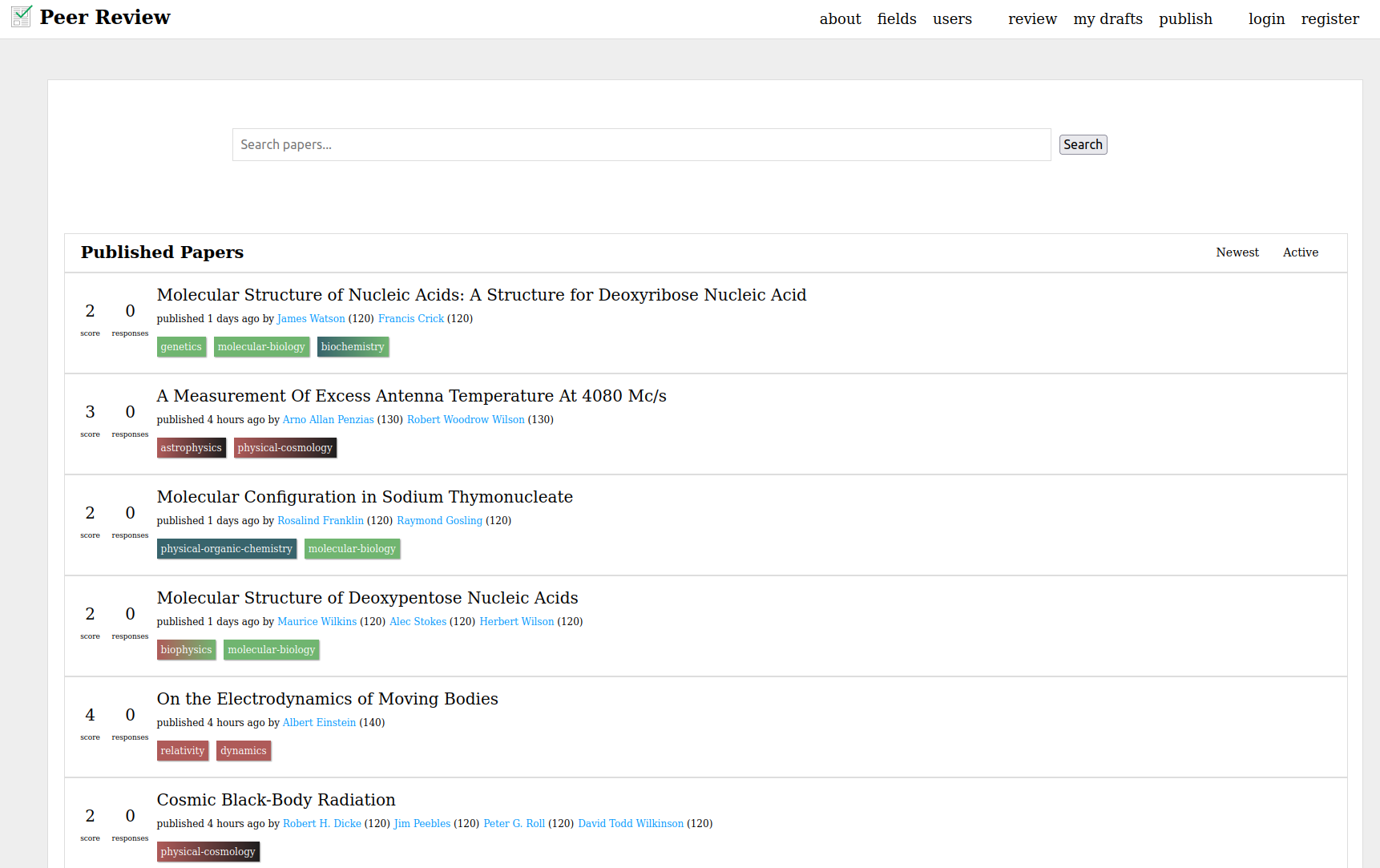

For two years I’ve been working to build a non-commercial scholarly commons. I first explored crowdsourcing review using a reputation system. About a year ago, I concluded that wasn’t going to work and I recently wrote up my reasoning in this post.

In late February, participants in the Recognizing Preprint Peer Review workshop posted a paper outlining a vision for preprint review. They examined how much progress we’ve made in the last 6 years, and it isn’t much. In my last post, I analyzed why.

Preprint review efforts suffer from the same impediments as crowdsourced review. Scholars simply do not have the time and they’re locked into the journals.

If we want scholars to adopt preprint review, or any other publishing experiment, we have to make it as frictionless as possible. We need to build it directly into scholar’s journal publishing workflow.

But the commercial publishers aren’t interested in reform. So can we bring the journals, and their authors and reviewers, to us?

Many Journals are Scholar Run

The journals are not the commercial publishers. The journals are their editorial teams and communities of scholars.

To get a sense of how many are entirely scholar run, I ran an unscientific survey. I looked at every Taylor and Francis journal in the Bioscience category (~300 journals) and assessed their editorial team. [1]

I found that ~53% of the journals I examined had no professional editor of any kind. Of the ones that did, it was often a grad student or research software engineer’s second job.

I spot checked Wiley, Sage, Elsevier, and Springer Nature using the same methodology. Sage, Elsevier, and Springer Nature appeared to show similar patterns, with most journals being scholar run. Wiley was the exception, consistently associating professional editors with its journals.

This suggests that there are a huge number of scholar run journals.

There are already a number of open source journal platforms. Why aren’t more editorial teams leaving the publishers to run themselves using these open source platforms?

It’s All About User Experience

User experience (UX) refers to the experience the user has while using a set of services or a product. In a non-software context, it is determined by interpersonal interactions, business processes, or a physical good. In a software or digital infrastructure context, the largest contributor to the user experience is the software’s interface.

In interface design, we have the concept of “friction”. Friction is anything that slows a user down: clicking, typing, thinking, or waiting. The best software user experiences are created by minimizing friction.

When building new software, you have to be aware of the market you’re building into. If there is no existing solution, then anything reasonably effective is likely to be adopted. But if there is an existing solution, then you can’t just match the existing experience. You have to substantially improve on it.

With the open source publishing platforms, we’ve seen them adopted by journal teams that have no where else to go. Editorial teams that can’t or won’t work with the publishers. But they haven’t been successful flipping journals. The user experience isn’t enough of an improvement on what the commercial publishers are offering.

The software is only part of the equation. Most editorial teams are given money to run their journals which many use to pay themselves a stipend. The publishers provide copy-editing, production, and marketing in addition to the software platforms.

We know user experience can make the difference. Negative user experience is the primary driver of the trickle of editorial defections. Can we build a user experience good enough to attract them?

How do we turn the trickle into a torrent?

Robert Maxwell established modern corporate publishing using a relentless focus on the user experience of editors. We need to invert what Maxwell did.

I’ve spent the last year conducting user research with editorial teams to learn how to flip them. As a starting point, I’ve identified a number of needs, most currently unmet by the open source platforms.

Save editors time.

Time is scholar’s most precious resource.

Neither Scholar One nor Editorial Manager are intuitive or low friction. Editors spend a lot of time providing technical support to their authors and reviewers. Sometimes going so far as to manually enter submissions because the authors or reviewers couldn’t figure out how to do it.

The open source systems are only marginal improvements. People working at library publishing programs shared similar stories of struggle.

Building a low friction, intuitive interface will save everyone involved time.

Handling editors often spend a significant chunk of their time googling for reviewers. Accurate reviewer recommendations would save them that time.

Many editors do a lot of their work outside of their systems. They communicate over email or Slack. They track their work in spreadsheets.

We know how to build powerful and flexible workflow and communication tooling. Having that tooling directly in their publishing platform would save editors additional time and cognitive load.

If we can save editors enough time, it could make the difference in their ability to adopt Diamond business models. I spoke with one editor who told me flatly “I wouldn’t do this job for free.” I asked her how long it takes her per week. “It takes 5 to 10 hours a week.” Is there a point at which she would do it on a volunteer basis? “Two to three hours a week.”

Focus on the community.

Journals are communities. They were 16th century social networks that have evolved to provide other services. The adoption of ResearchGate, Academia.edu, and Academic Twitter shows there’s a desire for a modern academic social network. Building publishing on top of a social network (think Github, not Facebook) would allow scholars to more easily find each other, communicate, and collaborate.

As it stands, authors have to re-enter their information into system after system. Editors have to build their own databases of potential reviewers, often from inaccurate data. Building publishing on top of a social network means authors and reviewers can enter their information once and editors will have access to it. This allows us to drastically simplify submission processes and help editors find reviewers more easily.

Many editors expressed a desire to do more to build community around their journals. We could provide a myriad of community building tools: discussions, Q&A, chat, documentation, and more.

Provide an Open Impact factor.

For better or worse (worse), Impact Factor is the standard metric by which journals are assessed. Leaving the commercial publishers usually means leaving the title, and its associated impact factor, behind.

If we want to give ourselves the best chance to de-commercialize publishing, we need to provide something that can make that easier to stomach.

We know how impact factor is calculated, meaning we can calculate an “Open Impact Factor” based on open sources. When whole editorial teams defect, we can count the old journal’s impact factor in the new journal’s OIF to give some continuity.

This won’t help us for the first flips, but if the scholarly community adopts the OIF, that would go a long way to enabling escape.

Replace publisher services.

Publishers are still providing copy editing, production, and marketing to all their journals. I did speak to some editorial teams that would be willing to forgo those services if it meant escaping the publishers to a better experience running their review processes, but other teams needed them. If we want to achieve universal non-commercial publishing, we need a replacement for them.

I don’t think it’s a good idea for the organization running the platform to directly provide those services. The goal is to build a commons to enable scholars to run their own journals, not a new publisher.

For copy editing and production, a better approach would be to automate them, provide inuitive tooling, or allow others to provide them through open marketplaces.

Marketing in this context is matching papers with interested readers. We can make marketing unnecessary by building powerful discovery tooling, ensuring that readers can always find the papers they’re interested in.

Democratic, not Decentralized

There is a push towards decentralized or federated systems, with good reason. But if we want to be successful, then we need to build this platform as a centralized system.

Mastodon still counts its total users in the low ten millions, and its average daily users in the low single digit millions.

We haven’t figured out how to build decentralized systems with low enough friction for the average user. Picking an instance is too much for most users and discovery remains an unsolved problem. We need to build a system that is easy and intuitive for any user, we can’t afford an architecture that introduces a bunch of friction at the outset.

The push for decentralization is really about the capital ownership of centralized systems. Capital ownership walls them off and inevitably enshitifies them.

But non-capital driven centralized systems don’t have to be walled gardens. We can open the source code for transparency (and contribution), open the data so that it can be reused, archived, and backed up, and open the API so that people can build on top of the system. We can enabled trusted partner institutions to run read-only mirrors.

Instead of decentralization, we need democracy.

We need non-profits that are governed by their users through directly democratic processes. We can write by-laws that require major decisions be ratified by a vote of the user base. Once there’s a reasonably sized user base, this would protect the system from take over by corporate interests.

Mirroring, open data, and open source provide an additional fail safe protection against take over, allowing the platform to be forked and carried forward in a new organization as a last resort.

Escape and Evolution

We can use flipping journals to bring the scholarly community to the platform, and then we can use the platform to make it low friction to participate in publishing experiments. In this way, we can help publishing evolve.

There’s a lot more to cover. Just building a platform isn’t enough. We need go to the journal editorial teams, convince them to leave the commercial publishers, and help them make the transition.

Some journal teams may be able to run very low cost to go Diamond. But others will need some way to fund their operations. Plus, we need to support the team building and maintaining the platform. We need to think about funding schemes, both for the platform and for those using it to organize publishing.

There’s still a lot more work to do. But I haven’t just been doing user research for the last year, I’ve been building an alpha.

That, however, is a story for another post.

- If any of the editors had the titles “Administrative Editor”, “Managing Editor”, or “Acquisitions Editor”, then I marked that as a professional editor. If I could identify any of the editors on LinkedIn and they listed T&F as an employer, I marked that as a professional editor. If the journal had a society affiliation, then I assumed professional editorial help through the society and marked it a “maybe”. I examined over 300 journals this way.