Why isn't Preprint Review Being Adopted?

This post is the second in a series about reforming academic publishing:

- Crowdsourced Review Probably Can’t Replace the Journals

- Why isn’t Preprint Review Being Adopted?

- How Can We Help Journal Editorial Teams Escape the Commercial Publishers?

Participants in the Recognizing Preprint Peer Review workshop posted a paper in which they outlined a vision for increasing peer review of public preprints. They, also, examined what progress has been made towards realizing that vision.

The paper shared data on the uptake in preprint review across 13 services. Some of the services listed use crowdsourced review, but most take a journal-like form with review organized and moderated by a team of editors.

You can find the raw numbers linked in one of the paper’s citations:

| Year | Articles Reviewed | Growth |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 23 | – |

| 2018 | 53 | 130% |

| 2019 | 317 | 498% |

| 2020 | 875 | 176% |

| 2021 | 1698 | 94% |

| 2022 | 2704 | 59% |

| 2023 | 3144 | 16% |

After 6 years, only a few thousand articles are being reviewed per year across 13 different services. And it looks like growth is stalling.

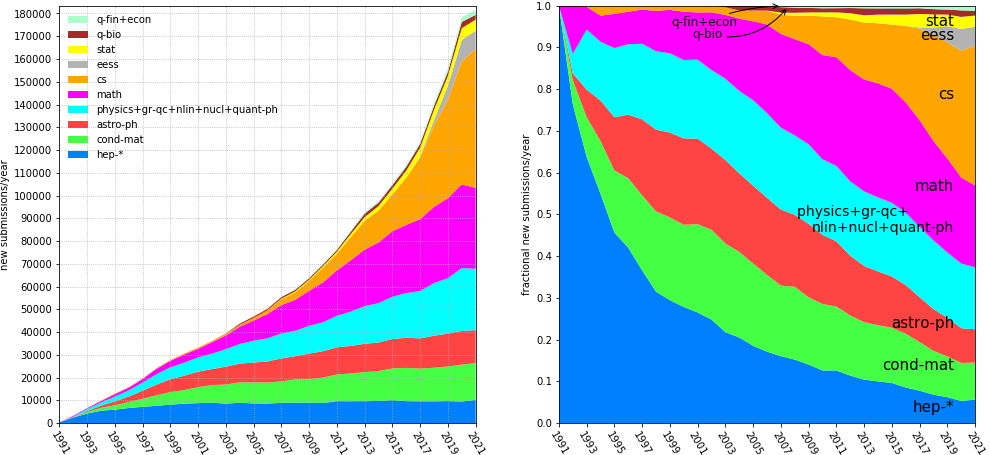

Compare that to Arxiv’s adoption:

After 6 years there were already 20,000 articles a year being shared through Arxiv - a single preprint service.

So why is the adoption of preprint review so much slower than the adoption of preprints themselves? And why does it appear to be stalling?

What’s blocking adoption?

All of these services suffer from two of the three impediments that prevent the adoption of crowdsourced review:

Scholars have no bandwidth for review and scholars are not free to leave the journals. The ones that crowdsource also suffer from fears of bad actors in an unmoderated context.

Scholars have no bandwidth for review.

They find time to review for traditional journals because it counts towards their service work and journal editors lean on personal relationships or the prestige of their journals, with an implied exchange of benefit. Journals are, also, communities and people will go above and beyond for their communities. Even with all of that, editors are really struggling to recruit reviewers.

Scholars are not free to leave the journals.

Scholars are required by their tenure and promotion committees to publish in a limited set of journals. They aren’t really free to go outside of their journals.

…so how did preprints get traction?

Preprints were able to get traction because they didn’t compete with journal publishing. There was a direct benefit to scholars from sharing their work through a preprinting service: they got it in the hands of their peers and community that much sooner. The time it took was low compared to the benefit. And they could still go on to publish it in a journal.

Preprint review does compete with journal review. It competes for scholar’s most precious resource – their time.

It doesn’t offer the same benefits as journal review. It’s not clear preprint review counts towards service work and the preprint review services don’t have prestige to lean on. They can’t offer an implied exchange of benefits. And they haven’t built significant communities yet (though many are working very hard to do just that).

Preprint review services have to ask academics to sacrfice their most precious resource in return for the promise of a better future.

We can’t afford to introduce additional barriers to adoption. But many of the preprint review services have done just that through their design choices.

Making it Harder than it Already Is

In user interface design, we have the concept of friction. Friction is anything that slows the user down in accomplishing their task: clicks, typing, thinking, or waiting. Some friction is unavoidable, but good system design always seeks to drive friction down to the absolute minimum possible.

Many of these services have introduced friction into the process of reviewing or seeking review for a preprint through their design choices. They chose to build new platforms to run preprint review and layer them on top of the existing preprint platforms, meaning adopters now have to contend with two entirely separate platforms.

Some of the platforms ask reviewers to select a preprint on a preprint platform, bring it to the review platform, and review it. Others ask authors to submit to an existing preprint platform before submitting to the review platform to have their paper reviewed.

To adopt preprint review through one of these platforms, users must:

- Become aware of the existence of a platform.

- Visit the platform.

- Understand what the platform is and what it is asking of them.

- Learn how to use the platform to give a review or submit a preprint for review.

- Find the preprint they want to review, or submit the preprint they want

reviewed, on another service. Meaning they have to:

- Discover the preprint platform(s) for their discipline. [1]

- Learn how to use the preprint platform.

- Find the preprint they want to review. Or submit the preprint they want reviewed and wait for it to be accepted.

- Learn how to submit that preprint to the review platform.

- If they’re the reviewer, execute the review. If they’re an author, they have to work through a journal-like review process.

At any point, we could lose a user. Each step in the journey adds friction and increases that risk substantially.

Some of these steps are unavoidable when you’re trying to build a new platform (eg. 1,2,3,4). Others we have direct control over. Step 5 adds a ton of friction not only to the initial adoption, but to each subsequent review and submission. COAR Notify helps with step 1 assuming the user is already on a preprint platform that has adopted it, but not the rest of the process.

By adopting these designs, we’ve made an already uphill climb that much steeper.

What can we do differently?

We need to make adopting preprint review as frictionless as possible. We need people to be able to do it with one click and for the option to do it to be right in front of them where they already are. We need to integrate preprint review directly scholar’s existing workflows. [2: eLife]

That means it needs to be a core part of the existing preprint platforms. Even better would be to integrate preprinting and preprint review directly into the traditional publishing flows and platforms: eg. Scholar One or Editorial Manager.

I’m assuming the folks working on preprint review tried to integrate directly into the *rxiv diaspora, and weren’t able to. It wouldn’t be surprising if the preprint services were wary of implementing review for fear the journals would view it as direct competition and start refusing to accept preprinted submissions.

It also seems highly unlikely that the commerical publishers are going to integrate preprinting and preprint review into Editorial Manager or Scholar One.

So are we stuck with high friction approaches? No. There’s a third option.

We can build a new platform, with preprinting and preprint review integrated directly into the publishing flow, and bring the journals to that platform.

The commercial publishers and the journals are not the same thing. The journals are their editorial teams and communities. Many (most?) of the editorial teams are composed of scholars. We’ve seen communities follow editorial teams when the editorial teams leave the commercial publishers.

If we could convince the editorial teams to run their journals on our new platform, they would bring their authors and reviewers with them. That would allow us to build preprinting and preprint review directly into scholar’s primary publishing workflow. We could make it one click and achieve the absolute minimum friction possible, which would give us the best chance of adoption.

So is that possible? Yes. But that’s a story for another post.

- Many of these services chose this architecture to take advantage of the buy-in that existing preprint servers have. They were hoping that this would eliminate steps 5.1 and 5.2. For those aware of the preprint platforms, that works. But step 5.3 still adds substantial, repeated friction to the workflow. And preprinting itself is still working towards adoption. By some estimates 5 million scholarly articles are published a year, but only 10 - 20 million preprints total have been shared in the last 30 years (wikipedia).

- There’s one service that doesn’t fit well into this analysis: eLife. By taking a traditional journal and turning it into a preprint review service, they are very nearly building preprint review into scholars existing flows… …nearly. They aren’t asking users to use two separate platforms, but they are asking users to choose between reviewed preprint and traditional VOR at the outset. They got some serious backlash from their community for doing it. It’s still early in the experiment, so it remains to be seen how it will play out. But of all the current attempts, this one removes the most barriers to adoption.